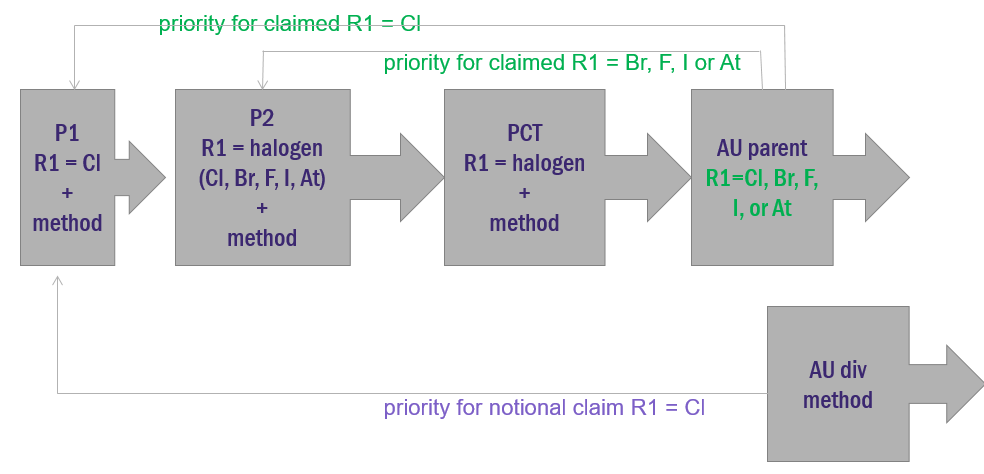

Poisonous priority is a phenomenon that arises when claimed subject matter is found to be anticipated by the application from which it claims priority or, in the case of a divisional, where a parent application is found to be anticipated by its divisional, or vice versa. Many in the Australian profession had considered that the Australian Patents Act did not give rise to poisonous priority situations.

In part 1 of this two-part series, we cover how an appeal decision of the Australian Federal Court opened the door to poisonous priority and provide a hypothetical example of poisonous priority.

In part 2 of this series, we consider how best to mitigate the risk of poisonous priority.

Mechanisms to avoid poisonous priority in Australia

There are mechanisms built into Australian law that can mitigate the effects of poisonous priority in certain circumstances. One such mechanism is Australia’s grace period provisions1 to remove the divisional from the prior art base of the parent. Thus, the one year grace period may save the patentee’s claim in the parent from invalidity. The practice of the Australian Patent Office2 is to allow the application of the grace period to whole of contents novelty situations. However, we have concerns with this practice.

Drafting considerations to circumvent poisonous priority

To best way to avoid falling foul of poisonous priority is to ensure that claims containing matter added after the initial priority date are kept apart from the earlier matter as a separate claim, or the later matter is set out as being a clear alternative in the claim itself. These approaches take advantage of the provision in the Australian Patents Act that allows for multiple priority dates to be assigned for each form of the invention defined by any claim3.

Thus, returning to our example contained in part 1, the poisonous priority issue may be avoided if the claims present the relevant feature, in this case the multiple possible halogens, as clear alternatives. This could simply be achieved by using “or” language in the parent claim.

The consequence of this is that a claim where R1 = chlorine retains the earlier priority date, whilst a claim to any other halogen has the later date, i.e. the date of the second priority application.

Whilst such a cautious approach as opposed to the first example may seem pedantic, the latter approach is more likely to ensure that the parent claim is construed as different forms of the invention, thus enlivening allocation of partial priority. This mitigates the risk of being viewed as mere variants of the invention as per AstraZeneca4.

Form vs. variant

While AstraZeneca is not an example of poisonous priority, the court considered different forms of the invention. The contentious amendment to claim 1 was the added disclaimer that “the counter anion to the inorganic salt is not a phosphate”. This amendment was found to be added subject matter and the question of post-dating arose, subject to the allocation of partial priority.

AstraZeneca argued for partial priority on the basis the unamended specification described pharmaceutical compositions which did not include phosphates as the salt forming anion and this disclosure would therefore provide basis for claim 1 to the extent that it claimed a pharmaceutical composition in which rosuvastatin was stabilised with an inorganic salt that did not include phosphate. According to AstraZeneca’s submission, a claim to such a pharmaceutical composition would be “one form of the invention” which would be entitled to the earlier priority date and not the later priority date of the amendment.

This argument was rejected by the court, which stated at paragraph 251:

“In our view, claim 1… does not define more than one form of the invention…claim 1…does not by its terms allow for any alternatives or, adopting the language of s 43(3), different forms of the same invention. Claim 1 defines only one form of the invention even though there will be any number of potential variants that are within its scope.” (Emphasis added)

Cases after AstraZeneca determined similar questions concerning form versus variant of the invention.

In Nichia Corporation v Arrow Electronics Australia Pty Ltd5, the main claim was to a light emitting device having a phosphor that contained a garnet fluorescent material including at least one element selected from the group consisting of Y, Lu, Sc, La, Gd and Sm, and at least one element selected from the group consisting of Al, Ga and In, and being activated with cerium. Dependent claim 3 limited claim 1 to the phosphor containing fluorescent material represented by a general formula (Re1-rSmr)3(Al1-sGas)5O12:Ce, where 0≤r<1 and 0≤s≤1 and Re is at least one selected from Y and Gd.

The Federal Court found that each claim envisaged and provided for different forms of the invention in the individual phosphors obtained after selection from the claimed ranges.

This approach was also adopted by the Patent Office in the case of Simco Mining Products and Services Pty Ltd v CQMS Pty Ltd6. The main claim was to an excavator bucket having a series of ratios defining dimensional aspects of the bucket. The key parts of the claim:

the ratio of lip width to side wall height in the region of said lip member is further in the range of from 2.5 : 1.0 to less than 3.1 : 1.0 and from greater than 3.6 : 1.0 to 4.4 : 1.0; and

the ratio of the length of the floor to the width of the floor is further in the range of from 0.8 : 1.0 to less than 1.0 : 1.0 and from greater than 1.25 : 1.0 to 1.6 : 1.0.

In assessing whether the various envisaged combinations of ratios represented different forms of the invention (thus enlivening section 43(3) and the allocation of different priority dates), the hearing officer considered the Nichia decision and stated at paragraph 136:

“I find a great deal of similarity between the ranges of claim 3 above and the ranges of, e.g., claim 1 of the [present] Application. Yates J placed considerable emphasis on the selections from the ranges as part of the “various selection steps [that] combine to provide differently constituted phosphors”. Following the same line of reasoning, I conclude that the steps of selecting the ratios from the respective ranges as defined in claim 1 will provide differently constructed excavator buckets, which I consider different forms of the invention within the meaning of subsection 43(3). Each of these different forms can have a different priority date.”

What this appears to suggest is that if the claim explicitly provides alternatives, i.e. using words like “or”, or provides ranges or combinations of ranges from which a selection is made, then the claim recites different forms of the invention. This affords allocation of partial priority thereby resolving the problem of poisonous priority.

Conclusion

Australian patent law provides for mechanisms to avoid poisonous priority under Australian law, by relying on the “grace period” where possible to exclude a patentee’s own related prior art. Given the limited applicability of the grace provision, a more prudent approach is to carefully consider any scope change to independent claims after the initial priority date, arising from added subject matter. Ensure that claims containing matter added after the priority date are kept apart from the claims to the earlier matter, or ensure that the later matter is set out as being a clear alternative in the claim itself.

1 Patents Act 1990, S 24(1).

2 Rozenberg and Co Pty Ltd. v Velin-Pharma A/S [2017] APO 61 & Biogen Idec Ma Inc. [2014] APO 25.

3 Patents Act 1990 S43(3).

4 AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 99

5 Nichia Corporation v Arrow Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 699

6 Simco Mining Products and Services Pty Ltd v CQMS Pty Ltd [2019] APO 5