Part 1 – The current situation in Australia

This is the first in a three-part series of articles on this subject, with the following two articles to be published in April and May.

Introduction

The patentability of methods of medical treatment has been a long debated issue in patent legislation, and different jurisdictions have taken very different approaches to this question. Issues around this subject are based not only on patent law but also on medical law, and the area is further complicated by the relevant ethical considerations, such as cost and access to medical treatment.

Patent protection for such inventions remains excluded in most parts of the world, but some countries have moved towards recognising the patentability of methods of medical treatment.

In Australia, case law has confirmed that medical methods are patentable. But there remains an unresolved question with regard to medical procedures – in other words, activities carried out by medical staff using medical equipment.

This series of articles looks at the history of patenting medical methods in Australia, provides a comparison with the approach of other leading jurisdictions, and explores the areas of remaining uncertainty and where the law may end up.

Before we get into detail, it is important to note that when considering patentability, a medical device or apparatus is treated exactly the same as any other product. If it is new and inventive then there is no bar to patenting. The exception may be a medical method invention that is ‘dressed up’ to take the form of a product, as we discuss later on in examples.

Australia – a brief history of patenting medical methods

In Maeder v Busch [1938] HCA 8 the High Court found it ‘very doubtful’ that a method or process of conducting an operation on the human body could be considered patentable subject matter. Such doubts were reiterated in the leading patent case concerning the nature of patentable inventions National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents [1959] HCA 67 (NRDC), where the High Court considered that methods of medical treatment of the human body are ‘essentially non-economic’, and therefore unpatentable.

As a result, the Australian Patent Office long considered methods of medical treatment to be ‘essentially non-economic’ or ‘generally inconvenient’.

The wind began to change in 1972 in the decision of Joos v Commissioner of Patents [1972] HCA 38. Here, the High Court overturned a decision by the Commissioner of Patents to refuse grant of a patent to a process for improving the strength and elasticity of keratinous material (human nails and hair), by applying a particular composition. The High Court distinguished this from a ‘method of treatment of a disease, malfunction, disability or incapacity of the human body or of any part of it’, which was unpatentable.

From that point on, with regard to cosmetic treatments (ie. processes or methods for improving or changing the appearance of a part of the human body, having a commercial application), such inventions were now considered patentable subject matter, and the Patent Office narrowed its patentability exclusion accordingly.

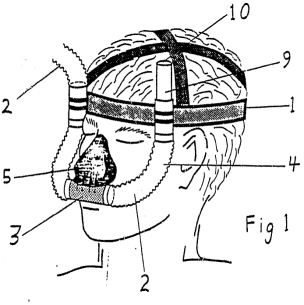

The patentability of methods of medical treatment was considered by the Full Bench of the Federal Court of Australia in Anaesthetic Supplies Pty Ltd v Rescare Ltd [1994] 50 FCR 1, relating to a patent for treatment of sleep apnoea. The Court held that there was no justification in law or logic, when considering patentability, to distinguish between a process of curative treatment of the human body to that of cosmetic treatment, and that both of these forms of treatment may constitute a manner of manufacture (provided they have commercial application).

Subsequently, in Bristol-Myers Squibb Company v FH Faulding & Co. Ltd [2000] FCA 316, the Federal Court of Appeal affirmed that methods of medical treatment of humans are patentable in Australia.

In light of these decisions, the Patent Office revised its position to accept that methods or processes for the treatment (medical or otherwise) of the human body or part of it to be patentable subject matter, and that no objection can be made on such grounds.

Recently, the High Court in Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 50 (Apotex) looked at the issue once again. At first instance, Sanofi-Aventis brought proceedings claiming that Apotex’s supply of a leflunomide formula to treat rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis infringed their patent. Apotex cross claimed seeking revocation of the Sanofi-Aventis patent on a number of grounds, including that a method of medical treatment of the human body was not a patentable invention. On appeal, the High Court (by a majority of 4 to 1) held that a method of medical treatment having useful application and economic utility, specifically the administration of therapeutic drugs to humans, constitutes patent-eligible subject matter in Australia. In particular, the court held (Apotex supra at [286]):

Assuming that all other requirements for patentability are met, a method (or process) for medical treatment of the human body which is capable of satisfying the NRDC Case test, namely that it is a contribution to a useful art having economic utility, can be a manner of manufacture and hence a patentable invention within the meaning of s 18(1)(a) of the 1990 Act.

But that’s not completely the end of the story. The Court acknowledged there is a distinction between such methods of treatment and the activities or procedures of doctors (and other medical staff) when physically treating patients, e.g. surgical procedures (Apotex supra at [287]):

There is, however, a distinction which can be acknowledged between a method of medical treatment which involves a hitherto unknown therapeutic use of a pharmaceutical (having prior therapeutic uses) and the activities or procedures of doctors (and other medical staff) when physically treating patients. Although it is unnecessary to decide the point, or to seek to characterise activities or procedures exhaustively, speaking generally they are, in the language of the NRDC Case, “essentially non-economic” and, in the language of the EPC and the Patents Act 1977 (UK), they are not “susceptible” or “capable” of industrial application. To the extent that such activities or procedures involve “a method or a process”, they are unlikely to be able to satisfy the NRDC Case test for the patentability of processes because they are not capable of being practically applied in commerce or industry, a necessary prerequisite of a “manner of manufacture”.

So this threw up a fascinating question – where would the line be drawn? What exactly is the patenting restriction so strongly signposted in Apotex? Did the Court mean that a process of physical steps carried out by a medical practitioner (eg. a particular novel sequence of surgical steps) was incapable of being applied commercially? Or did it suggest that the new use of a known apparatus would be excluded from protection. If so, would that apply to (say) the application of a particular type of pump, known for use in one part of the body, to another part of the body, where that use would not be obvious?

We note that the above excerpt from Apotex was obiter dicta, however the Australian Patent Office has started to rely on it in issuing objections to certain applications.

Looking back at Anaesthetic Supplies v Rescare, the primary method claim at issue was claim 9:

A method of treating snoring and/or obstructive sleep apnoea in a patient comprising: applying air through a nose piece at a pressure maintained slightly greater than atmospheric substantially continuously throughout the breathing cycle.

The only apparatus in the claim is a nose piece, clearly a well-known piece of equipment, so the invention was a classic example of a new use of a known product, namely a new mode of air delivery, via a known device (a nose piece), to treat a particular ailment.

So, if that case is correct, how is that distinguished from the situation discussed by the High Court in Apotex? Well, firstly the sleep apnoea treatment is non-invasive. Secondly, it might well not be carried out by a medical professional (it could be a machine for home use by the patient at night). But either way, why should that distinction affect whether the process is seen as a method capable of commercial application, while other medical processes are not?

In Part 2 of this series of articles to be published in April, we look at the different approaches Europe and the US have adopted in regards to this type of invention.