Introduction

Meat ‘grown’ in the lab – would you try it? You might see it on the shelf earlier than you think. Lab‑grown meat could represent as much as 0.5% of the world’s meat supply by 2030 – millions of tonnes of food.

Cellular agriculture for food production is a rapidly growing field aimed at targeting vegetarian and vegan audiences, but also combating global food security and climate change challenges. Creating non-traditional food products by using biotechnology will be particularly important for generating diversified protein sources to meet global demand.

Significant advances in stem-cell and recombinant technologies in recent years sets the foundation for further innovation to create the food of the not-so-distant future. As such, cellular agriculture food products are predicted to have an Australian commercial market of AUD$105-210 million by 2035, and multiple companies and university research groups across Australia focus upon lab-grown food.

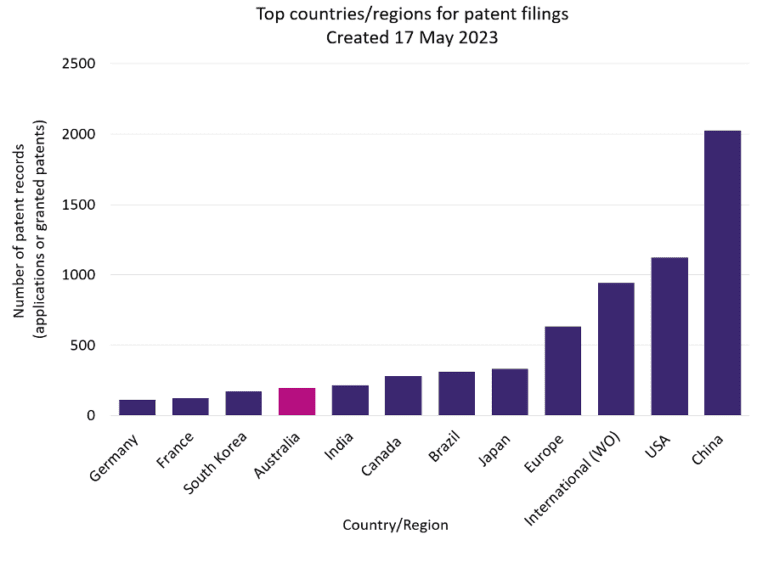

Australia is in the top ten jurisdictions for national patent filings in the field of cellular agriculture technology. However, Australia appears to be underperforming compared to other major jurisdictions, particularly China – currently leading the way by a significant margin (Figure 1). And in Southeast Asia, Singapore is rapidly establishing itself as a world leader in non-traditional protein industries (although this is not yet reflected in national Singaporean filings, Figure 1). But there is great potential for Australia to compete with other jurisdictions. With Australia’s close proximity to Asia and ripe ground for scientific innovation, Australia’s commercial and intellectual property footprint in the cellular agriculture space can only be expected to grow going forward.

Figure 1: A graphical comparison of patent records in the cellular agriculture space (including cultivated meat, precision fermentation, and biomass fermentation).

With these scientific and commercial developments in mind, this article discusses considerations for patent protection around cellular agriculture technology.

What is cellular agriculture in terms of food?

Cellular agriculture for food production encompasses many biotechnology and synthetic biology processes for ‘growing’ animal-derived food products (e.g. meat, dairy) or components (e.g. proteins, fats, sugars, flavours) in the lab. This encompasses the biotechnological production of alternative proteins, and also lab-grown meat that contains non-alternative, naturally occurring meat proteins.

The CSIRO identified in their future “Protein” roadmap two prominent areas for the development of novel food production systems3:

- Cell cultivation (also known as cultivated meat), where stem cells are cultured into a meat product. The stem cells can be fat or muscle stem cells, or induced-pluripotent stem cells differentiated towards fat and muscle cells and proliferated, as required. The key difference between cultivated meats over existing alternative meats that are exclusively made from alternative proteins, is that cultivated meats have the potential to directly ‘replicate’ animal meat, because they are based on grown animal cells. Cultivating meat in the lab also gives the opportunity to add flavour enhancers and/or nutrients to improve the end meat product, and to produce meat products derived from animal that are not traditionally farmed. Examples of cultivated meats currently being explored include the usual suspects chicken, beef, pork, lamb and seafood but also kangaroo, crocodile and alpaca.

- Precision fermentation, which is designed to generate a specific food component that is then extracted from the microorganism used to ‘brew’ the component. Precision fermentation can utilise recombinant fungi, algae or even bacteria to produce required plant or animal molecules, the caveat being that the molecules must be safely extracted and purified for human consumption. Examples of precision fermentation include lactoferrin breast milk protein for baby formula produced by yeast.

A third aspect of cellular agriculture is biomass fermentation. Unlike precision fermentation, the microorganisms undergoing biomass fermentation become the food product themselves, rather than having the food product extracted from them. A common example of this already on the market is the alternative-protein based meat substitute ‘Quorn’, based on filamentous mycelium harvested for their high mycoprotein content.

Hybrid technologies combining multiple aspects (e.g. precision fermentation + cell cultivation) are also emerging. Further, cell-based products can complement existing plant-based or fermentation‑derived products.

Whilst these technology areas herald exciting changes to the food landscape, challenges faced by the sector include:

- identifying suitable cellular sources for fermentation and/or culturing;

- culturing stable cell lines and ensuring correct differentiation of cell types;

- synthesising difficult ingredients;

- maintaining taste and texture to appeal to consumers;

- cost-effectiveness;

- quality control;

- food safety; and

- scalability

But with each challenge comes opportunity – opportunities for further innovation, and subsequently patent protection.

What aspects of cellular agriculture may be eligible for patent protection?

Numerous aspects of cellular agriculture may be susceptible to patent protection. For example:

- recombinant or isolated peptides, polypeptides, nucleic acids, vectors, cells

- novel microbial strains

- novel genetically modified plants or animals

- food composition, components, and mixtures such as:

- nutrients

- flavours, additives and preservatives

- precursor molecules

- biomaterials

- engineered animal proteins eg haeme-containing proteins, insect proteins

- engineered plant proteins eg algal, soy, pea, hemp

- engineered fungal proteins

- engineered milk proteins eg whey, casein

- cell-based food products such as:

- meat replicas or substitutes

- seafood replicas or substitutes

- dairy replicas or substitutes – milk, cheese, yoghurt

- artificial breast milk

- bioreactor design and devices

- culturing components eg growth factors, culture media, cryoprotectants

- scaffolds and supports

- methods of:

- culturing cells

- modifying or differentiating cells

- fermentation

- purification and extraction

- generating cell scaffolds or supports

- 3-D printing or growing cells on scaffolds or supports

- producing proteins or compounds

- producing/formulating food products

General requirements for patenting in this space

To obtain a patent to an invention, the invention must be:

Novel – The invention must be new compared to the “prior art”. Any non-confidential disclosure can form part of the “prior art” against which novelty is assessed. As such, it is essential to be aware of and manage self-disclosures e.g. inventors’ publications, presentations, public or online announcements etc.

Ideally, a patent application should be filed before the invention is publicly disclosed. If a disclosure of the invention has been made, it may be possible to navigate the disclosure by filing a patent application within the ‘grace period’ (usually six to twelve months) from the disclosure in certain jurisdictions. However, it should be kept in mind that some important jurisdictions, notably Europe, do not currently provide a grace period and therefore inventors and applicants should not aim to rely on the grace period to correct loss of novelty through premature disclosure of the invention.

Inventive – The invention must be non-obvious. Patent examiners assess if the invention would be obvious to a hypothetical person of ordinary skill in the field of the invention (the skilled person). The assessment of inventiveness differs across jurisdictions, including major jurisdictions like Europe and the US.

Prospects of successfully demonstrating inventiveness/non-obviousness can be increased by pointing to advantages of the invention over the prior art. For example, if the invention is a method, does the method provide increased efficiency, increased safety, and/or better yield? Are aspects of the method not routine or straightforward? For products, does the food composition or component have improved features e.g. better taste, nutritional value, integrity, texture; or any other surprising or unexpected benefits? It can also be very useful to include data within the patent application directly contrasting advantages of your invention against existing methods/products.

Supported and enabled – There must be sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the invention works, and the invention must be described with enough information that a person in the field would be able to perform the invention. Importantly, the information included within the patent specification directly influences how narrow or broad the claims can be, impacting the scope of the monopoly that a granted patent would provide.

Patentable subject matter – The subject matter of the claimed invention must not be legally excluded from patentability. Patentable subject matter requirements vary in different countries, including across major jurisdictions.

Challenges can arise if aiming to patent cells, nucleic acid sequences, protein sequences or other naturally occurring substances, particularly if the cell, sequence or substance has not been modified compared to its naturally occurring form. Patentable subject matter is an important consideration, particularly in the US where patenting of inventions directed to naturally occurring substances can be challenging. The team at FPA will be able to appropriately advise you as to the options and strategies for obtaining patent protection if your invention relates to a naturally occurring substance.

A further important consideration for patenting food or drink innovations is the patent eligibility of mixtures. If the composition is a mere mixture of known ingredients where the ingredients are each behaving as per their inherent properties, or the method is a process producing such a composition by mere admixture, then it may not constitute patentable subject matter (depending on the jurisdiction). This can sometimes be overcome by demonstrating an interrelationship between the elements in a mixture – for example, one ingredient reduces the acidity of another.

Conclusion

- Cellular agriculture is an exciting field ready to diversify food production worldwide.

- Key biotechnology areas in this space include (but are not limited to!) cultivated meat, precision fermentation and biomass fermentation.

- New and inventive cellular agriculture methods and/or food compositions, components and products can all be inventions worth capturing in a patent application.

- Key considerations for patenting cellular agriculture inventions are: novelty, inventiveness, ensuring sufficient information within the application to support and enable the invention, and the eligibility of cells and biologicals for patent protection in different countries.

If you are interested in patent protection in the area of cellular agriculture, please get in touch with our ChemBio team.

1 “Cultivated Meat: Out of the Lab into the Frying Pan” Tom Brennan, Joshua Katz, Yossi Quint, and Boyd Spencer, 2021, accessed 28 September 2022: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/agriculture/our-insights/cultivated-meat-out-of-the-lab-into-the-frying-pan

2 “Cellular Agriculture: An Opportunity to Diversify Australia’s Food System”, Cellular Agriculture Australia, 2022, pp 7-8.

3 CSIRO Futures (2022) Protein – A Roadmap for unlocking technology-led growth opportunities for Australia. CSIRO, Canberra.