In the second of this three part series, this article focuses on the plausibility requirement of enablement and considers the path that Australia is likely to follow in assessing enablement (part 1).

The higher threshold standards introduced via “Raising the Bar” in 2013 to the Australian Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (“the Act”) brought about changes to the enablement provisions in order to align standards with those of Europe and the UK. Whilst we await case law from the Australian courts1 to guide the interpretation of enablement and support, a number of recent Patent Office decisions provide some guidance in implementing the enablement provisions.

Case study – how the Patent Office is assessing plausibility

The most recent of those decisions, Gary B Cox v MacroGenics, Inc. (“MacroGenics”)2 related to opposition of patent application AU 2012259162, an application directed to deimmunised serum-binding domains and their use for extending serum half-life of therapeutic polypeptides. Increased half-life is achieved through the conjugation of a therapeutic polypeptide to an albumin-binding domain (ABD) which binds to serum albumin, increasing the size of the polypeptide and rendering it is less likely to be filtered from the body.

The claim opposed for lack of enablement defined a polypeptide comprising a deimmunised ABD that differed from the wild-type version by comprising triple mutations at amino acid positions 64, 65 and 71 (the “AAA” mutation), or triple mutations at amino acid positions 66, 70 and 71 (the “DSA” mutation). Mutations to these residues of the ABD prevent an otherwise detrimental immunogenic response. The claim also required that the albumin-binding protein portion extend the serum half-life of the polypeptide, as described above.

Key to the decision was the construction of the claim – that is, the claim was not limited to a polypeptide containing only the AAA or DSA mutations to the ABD, but because the “open” or “inclusive” comprising language encompassed ABD variants having any number of mutations. Thus, the key consideration was whether the scope of the claim, which encompasses variants of ABD having any number of mutations, was enabled by the disclosure in the specification.

The Act (post “Raising the Bar”) requires that a patent specification disclose the invention in a clear enough and complete enough manner such that the person skilled in the art must be able to perform the invention across the scope of the claim without undue burden or inventive skill.

The relevant test and how it was applied

As applied in MacroGenics, the Patent Office appears to be settling on a three-part test, developed through European and UK case law:

- What is the scope of the invention as claimed?

- What does the specification disclose to the skilled person?

- Does the specification provide an enabling disclosure of all the things that fall within the scope of the claims, and in particular:

- Is it plausible that the invention can be worked across the full scope of the claim?

- Can the invention be performed across the full scope of the claim without undue burden?3

Consistent with the Act’s intention to align enablement standards with those of the UK and Europe4, the Delegate took guidance from Warner-Lambert Company LLC v Generics (UK) Limited(t/a Mylan) and ors (“Warner-Lambert”)</em class=”footnote”>5 and considered plausibility a low threshold test that requires the specification to disclose some reason for supposing the implied assertion of efficacy in the claim is true. Whilst it is not just a bare assertion, it must be based on reasonable scientific ground such that a skilled person would think there was a reasonable prospect that the assertion be true, based on their own knowledge and the teaching of the specification. In other words, it amounts to a test of technical credibility.

In Warner-Lambert, the claims that were directed to the treatment of neuropathic pain were found on appeal to lack plausibility. Based on the disclosure, it was considered that treating certain types of neuropathic pain satisfied the plausibility requirement, but that it was not plausible to predict that pregabalin would be efficacious for treating all neuropathic pain.

Turning to the consideration of plausibility in MacroGenics, the low threshold requirement of plausibility worked to the Applicant’s advantage. Because ABD variants satisfying the functional requirements of the claim could be identified and used to extend polypeptide half-life, this arm of enablement was satisfied. This was however a separate consideration to whether a skilled person would be subject to “undue burden” in practising the claimed invention. Indeed, a claimed invention that is plausible may still lack enablement if the working of the claimed invention would require a research program or experimentation that requires inventive skill and amounts to undue burden.

In MacroGenics, whilst the claimed invention was found to be plausible, it was established that identification of variants that are both deimmunised and have an increased half-life, while routine, would be unpredictable. As the specification provided no teaching of additional mutations that could be made whilst retaining the features of increased half-life and deimmunisation, the Delegate concluded that there would be an undue burden to work the invention across the scope of the claims, and thus that the specification failed on the higher threshold “undue burden” requirement of enablement. The “undue burden” aspect of enablement is discussed in part 1 of this series.

The MacroGenics case is not the first Australian Patent Office decision to consider plausibility as a requirement under enablement. In the Evolva case6, the issue was whether it was plausible that the defined UGT polypeptides, which have as low as 90% identity, would be capable of catalysing the defined glycosylation reaction in the production of artificial sweeteners, called mogrosides. Given the prior art knowledge of the structure and function of UGTs, it was established that a skilled person would consider it plausible that functional variants to a level of identity of at least 90% could be identified and would be useful in the defined process.

Although we cannot be certain as to the path the Australian courts will take in assessing enablement, it appears more likely than not, that they will follow the path of the UK courts. Although both Australian Patent Office decisions have found the relevant claimed subject matter to be plausible, the findings in the aforementioned Warner-case provide some guidance on the possible threshold of the plausibility requirement that may extend to Australian law.

Practical considerations

Only time will tell if Australia is to take guidance from the UK courts in assessing plausibility, however there is no strong reason to believe that they will not do so. The specification should be drafted keeping in mind the following considerations:

- It should be evident that a given product would be efficacious for the treatment of a given condition. A mere possibility or bare assertion is unlikely to be sufficient. Rather, a disclosure of reasonable scientific grounds that amount to an expectation that it might well work is recommended.

- Although the disclosure need not definitively prove the assertion that the product works for the designated purpose, a skilled person must glean from the specification a reasonable prospect of the assertion to be true. Experimental data is not absolutely necessary to demonstrate the effect on the disease process, although would be extremely helpful.

- Whilst the disclosure may be supplemented with a skilled person’s knowledge, the skilled person must still derive the plausibility from the teachings of the specification.7

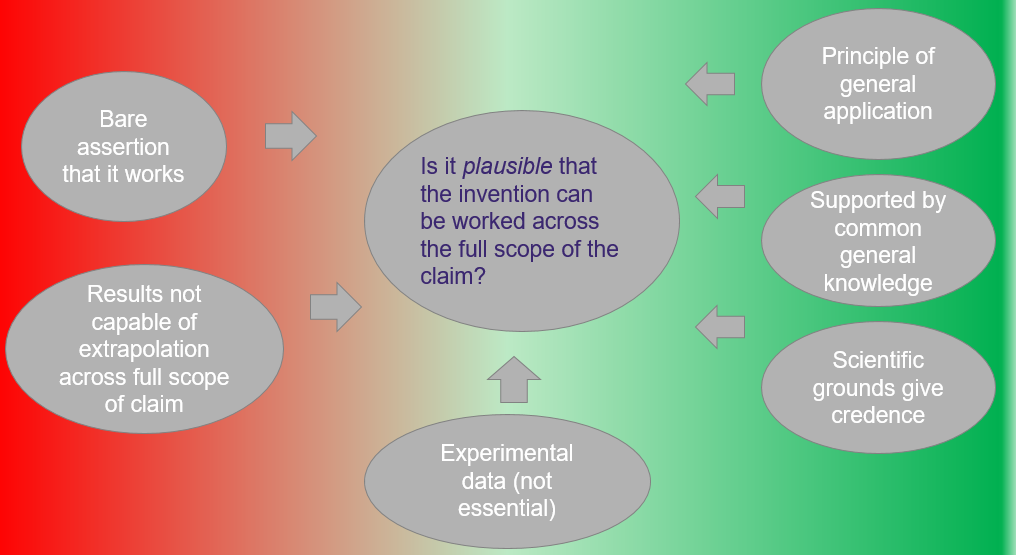

By way of summary, this diagram depicts some of the considerations taken into account in assessing the plausibility question, where the red to green scale is indicative of a possible negative to positive outcome to the central question.

Figure 1: Current position of plausibility requirement under Australian Patent Office decisions.

1 The Federal Court in Encompass Corporation Pty Ltd v InfoTrack Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 421 provided little guidance on enablement and support and we await the Full Court decision for further enlightenment.

2 Gary B Cox v MacroGenics, Inc. [2019] APO 13

3 Ibid

4 The Explanatory Memorandum, Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Bill 2011, item 8.

5 [2018] UKSC 56

6 Evolva SA [2017] APO 57

7 Warner-Lambert Company LLC v Generics Ltd t/a Mylan and another [2018] UKSC 56 at 37