This article originally featured in IAM’s winter 2019 edition, Patents In Asia.

Why file in Southeast Asia?

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which comprises Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam, is a thriving region. With a gross domestic product of $2.92 trillion in 2018 and a population of almost 650 million – 9% of the world’s population – it is a significant emerging market, with diverse and expanding industries. In addition to some of the more traditional manufacturing sectors, the ASEAN member states are becoming globally competitive and attractive to foreign investors in a wide range of industries:

- the healthcare market for pharmaceutical and medtech companies represents an enormous growth opportunity, with the increase in spending expected to exceed that of Brazil, Russia, India and China in the next few years;

- the electronics sector has seen rapid and sustained expansion over the past five years, with more competitive offerings by exploiting, for example, the rising labour costs in countries such as China;

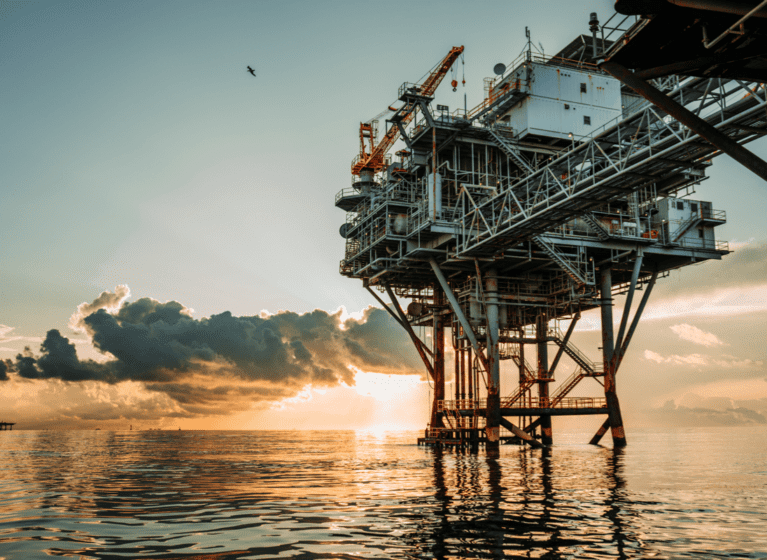

- ASEAN member states are playing an increasingly important role in the chemical sector, from speciality chemicals to petrochemicals, not just in respect of production, but also with regard to their R&D capabilities;

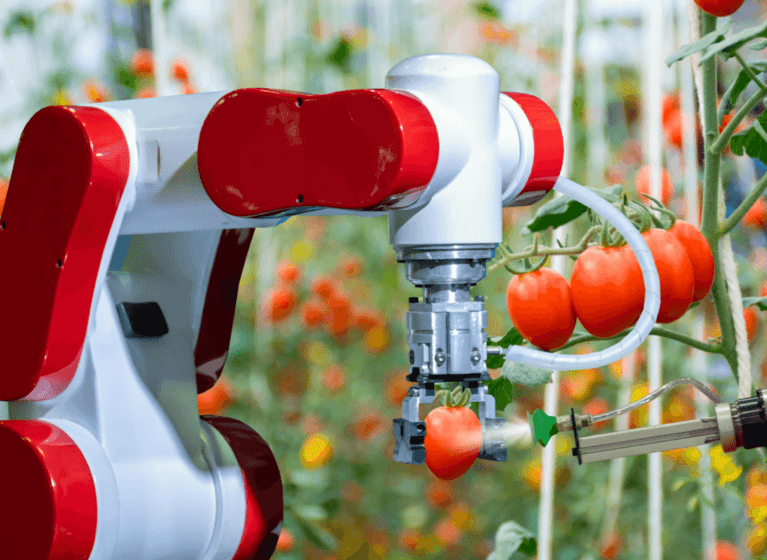

- agriculture is one of the biggest industries there. However, with the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community in 2015 and the opening up of free trade between members, agribusiness is an emerging market that goes beyond employing and feeding citizens of the region;

- energy-related challenges and the aim to lower reliance on fossil fuel imports has seen a boom in the energy and cleantech industries in Southeast Asia. The need for alternative and cheaper fuels, renewable and clean energy and pollution reduction, combined with lower market-entry barriers for foreign investors, are driving the development of this sector; and

- Southeast Asia has become a leader in the automotive industry. Most major car companies have manufacturing, and in many instances engineering design centres there, which cover everything from car and part production and export to R&D facilities for vehicles powered by alternative fuels and autonomous vehicle technology.

This diversity and increased recognition of the value of this region is further reflected by almost 250 companies choosing to have their headquarters in one of the ASEAN member states – a fivefold increase in less than a decade. It is thus little surprise that global recognition of this burgeoning and increasingly important market has resulted in an unprecedented interest in Southeast Asia as a patent filing destination. Foreign applicants file six to 10 times more applications per year compared to locals, and the percentage of these applicants filing in the ASEAN member states is increasing each year. However, filing IP rights in Southeast Asia includes more formalities, fewer electronic records and online processing and developing patent systems and laws. This is combined with logistical issues (eg, different time zones from Europe and North America, non-English correspondence and a general lack of knowledge of the Southeast Asian business environment and cultural differences). Moreover, unlike Europe and other economic regions, Southeast Asia is multi-jurisdictional – there is no regional patent. And this raises the question – how best to manage a patent portfolio across this region?

A regional patent prosecution model

Patent prosecution on a country-by-country basis is plagued by inefficiencies. Eligibility criteria for jurisdictions is largely aligned with the rest of the world – novelty, inventiveness and utility. Accordingly, the degree of overlap and similarity of prior art objections raised in each jurisdiction results in the same response instructions having to be sent out repeatedly. However, laws have not been completely harmonised and formality-type objections are highly variable between Southeast Asian countries. Thus, a one-size-fits-all response does not work either. One option is to use one firm to manage the filing and prosecution of all of the applications for the region – it means that companies have a single point of contact and that one attorney or team of attorneys has oversight over developments in all relevant countries. In particular, such a strategy can facilitate:

- pre-emptive prosecution strategies for avoiding or overcoming formality objections;

- proactive, coordinated claim strategies that rely on claims allowed in jurisdictions such as Australia, Europe and the United States, amended to ensure conformity with each of the local laws – this approach typically results in claims proceeding immediately to allowance, thereby saving time and costs associated with one or two rounds of prosecution;

- a consistency-of-claim approach and scope to protect key commercial assets. This is an increasingly important consideration in light of the movement of goods between ASEAN member states and the potential distribution of infringing goods; and

- forward planning where a divisional strategy is intended in light of the often-strict laws on overlapping subject matter. And importantly, adequate forewarning of the divisional filing deadlines which vary widely, from as soon as within three months of the first substantive examination report in Malaysia, to prior to grant fee payment in countries such as Singapore.

Patentable subject matter

Like so many other jurisdictions, Southeast Asia has seen a shift in the past few years as to what subject matter can be pursued, particularly with regard to natural products, diagnostic methods, treatment systems and computer-implemented inventions. All of the Southeast Asian jurisdictions are hesitant around patent claims to methods of medical treatment. Vietnam and Indonesia both recently updated their laws to restrict medical use claims – whether they be purpose-limited use claims as per the current EPO approach or the older style ‘Swiss form’ claims. But for the remaining jurisdictions, a Swiss form claim (or variation thereof) is acceptable subject matter. It is for this reason that an Australian application, which can contain Swiss form claims, is better placed than a US or European application as the basis for the regional prosecution model. Filing claims directed to naturally occurring products and diagnostics that have been allowed in Europe and Australia has generally been acceptable to most Southeast Asian patent offices. However, in Thailand, extracts from animals cannot be patented. Inventions to cells, for example, may attract an objection. Further, the IP Office of Singapore only permits naturally occurring products that comply with their recently implemented patentability guidelines discussed below.

In light of court decisions around the world, the IP Office of Singapore has proactively sought to clarify the distinction between, and therefore the patentability of, isolated or purified materials or microorganisms that can be found in nature. While yet to be tested in a court, examination takes the following approach:

- isolated or purified materials or microorganisms that can be found in nature are discoveries and not considered to be an invention;

- however, a new use of an isolated or purified material or microorganism can be claimed;

- a modified isolated material or microorganism (and its use) can be claimed if the modification results in a material or microorganism that can be clearly distinguished from the naturally occurring material or microorganism;

- an in vitro diagnostic method based on novel biomarkers performed on blood samples obtained from patients is an invention if it represents a specific application of a discovery which allows the diagnosis of a disease to be made; and

- a claim directed at a process that occurs in nature is not allowable, but if a new application of the process is found, then the new, specific application can be claimed.

Patent eligibility of computer-related inventions continues to be assessed on a country-by-country basis. Standards and requirements across countries in Southeast Asia differ, and depend on context. Computer programs per se are not patentable, although it varies between jurisdictions as to whether it is an explicit exclusion or whether they fail to meet more general patentability standards. But computer-implemented inventions generally are patentable, provided that the program makes a technical contribution to the invention. For example:

- In Thailand, Malaysia and Vietnam, inventions relating to devices or machines controlled by software may be patentable if the computer program provides a technical effect that contributes to the invention.

- Indonesia’s patent law was clarified in recent years to exclude “rules and methods that only contain computer programs”. So like other jurisdictions, an invention where the computer provides a technical effect so as to solve a problem may be patentable.

- The examination guidelines in the Philippines require one or more of the features of the invention to be realised by means of a computer program.

- In Singapore, examiners are advised to consider the extent to which the computer contributes to the invention defined in the claims and that it is integral to the invention.

Most Southeast Asian countries also prohibit scientific and mathematical methods and theories, which makes it challenging to protect business methods. But again, context may provide patentability.

Is my Southeast Asian patent worth the paper it is written on?

There is no question that quality now eclipses quantity, regardless of the country. Enforceability and valuation have become increasingly important parameters in an age where companies may be looking at either a buyout or an initial public offering as an exit strategy, and where the commercial value/success of the invention attracts attention from those seeking to invalidate it. From the Southeast Asian perspective, there is a clear recognition that strong and enforceable IP rights play an important role in encouraging transfer of technology, stimulating innovation and creativity, and influencing the implementation of trade policies that will create more competitive domestic markets for foreign companies. With this comes a commitment from the ASEAN member states to further improve their own and regional IP systems. An ASEAN Intellectual Property Rights Action Plan 2016 to 2025 seeks to transform the region into an innovative and competitive region through the use of intellectual property, via its four goals to:

- develop a more robust ASEAN IP system by strengthening IP offices and building IP infrastructures;

- develop regional IP platforms and infrastructure via IT upgrades and online processes;

- expand the ASEAN IP ecosystem to:

- build respect for intellectual property; and

- enhance cooperation on regional IP rights enforcement, among other things; and

- enhance regional mechanisms to promote asset creation and commercialisation and promote IP rights protection and commercialisation.

So returning to the original question – why file in Southeast Asia? It is almost 10% of the world, with diverse and growing markets and industries. The implementation of trade policies will create more competitive domestic markets for foreign companies. And while the member states acknowledge that enforcement remains a challenge, this is not an issue unique to Southeast Asia and the ASEAN members and it should not be a deterrent.